Gastroparesis Life Expectancy: What to Know

When people search for gastroparesis life expectancy, they’re usually asking two things at once: “Will this condition shorten my life?” and “What can I do to live well with it?” Gastroparesis is a chronic stomach-motility disorder that ranges from mild inconvenience to severe, life-limiting disease. The short, evidence-based answer is that gastroparesis most commonly reduces quality of life rather than lifespan — but serious complications (malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, recurrent hospitalizations) and underlying diseases (especially long-standing diabetes) can increase health risks and shorten life expectancy in individual cases. This article explains what gastroparesis is, how it’s diagnosed and treated, what affects long-term outcomes, and practical steps patients and caregivers can take to preserve both health and quality of life.

What is Gastroparesis? A quick primer

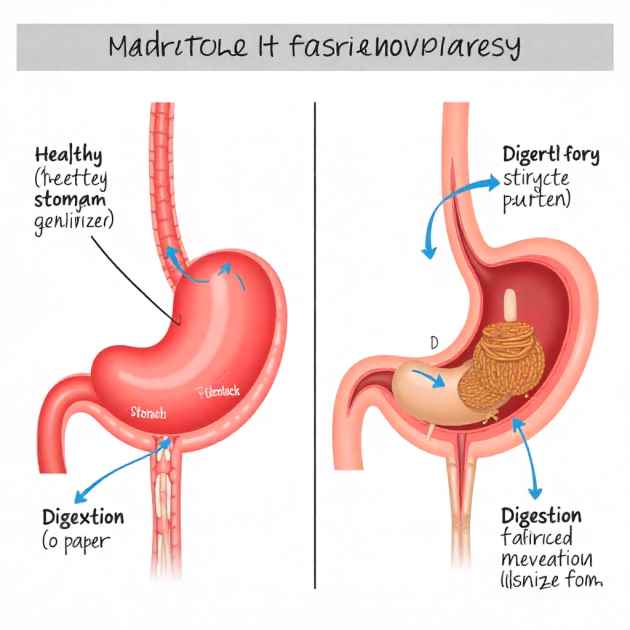

Gastroparesis refers to a condition known as “stomach paralysis.” People with this issue experience a delay in the stomach emptying process, which happens without any physical obstruction in the stomach or intestines. The small intestine. Normal digestion relies on coordinated muscle contractions and nerve signaling to move food from the stomach into the small intestine. In gastroparesis this process is impaired: food stays in the stomach longer than it should, causing nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and often poor appetite.

The disorder is a functional motility problem rather than a structural blockage. Severity varies widely: some people have intermittent mild symptoms managed with diet changes, while others lose weight, suffer recurring hospital admissions, or require long-term enteral feeding (tube feeding). Because gastroparesis affects digestion, hydration, and drug absorption, its consequences can ripple into other medical problems — and those interactions are central to understanding gastroparesis life expectancy.

Causes & Types (diabetic, idiopathic, post-surgical, medication-induced)

Gastroparesis is not a single-disease entity; it has several common causes and patterns:

- Diabetic gastroparesis: One of the most common causes. Long-standing high blood glucose can damage autonomic nerves (including the vagus nerve), impairing stomach motility. In people with diabetes, the severity of neuropathy and blood-sugar control influence symptoms and outcomes.

- Idiopathic gastroparesis: When no clear cause is found, diagnoses are labeled idiopathic. It is common for idiopathic cases to occur, and they can often be long-lasting. Some idiopathic cases may eventually be linked to prior viral infections or subtle neurologic disorders.

- Post-surgical gastroparesis: Abdominal or vagal nerve injury during surgery — for example, after certain gastric or upper abdominal procedures — can cause delayed gastric emptying.

- Medication-induced gastroparesis: Several medications slow gastric emptying as a side effect (opioids, certain antidepressants, some anticholinergics, and others). Stopping or substituting the offending drug often improves symptoms.

- Secondary causes: Systemic conditions such as connective tissue diseases, neurologic disorders, amyloidosis, or hypothyroidism can also affect gastric motility.

Understanding the cause is crucial because it guides treatment choices and informs prognosis. For instance, diabetic gastroparesis often coexists with other diabetes complications that influence long-term health, while medication-induced cases may resolve with drug changes.

Symptoms and How Severity is Measured

Common symptoms of gastroparesis include:

- Persistent nausea and intermittent or recurrent vomiting

- Early satiety (getting full after small amounts of food)

- Bloating and upper abdominal discomfort or pain

- Weight loss and unintentional malnutrition in severe cases

- Fluctuating blood glucose control in people with diabetes due to unpredictable absorption of oral intake

Severity assessment typically combines patient-reported symptom scales, objective tests of gastric emptying, nutritional markers, and the presence of complications. Symptom scoring systems (used in clinical trials and clinics) quantify nausea, vomiting frequency, bloating, and impact on daily activities. Objective measurements consist of the percentage of food that remains in the stomach at certain times throughout a gastric emptying test. Nutritional status — weight trend, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin, and vitamin/mineral levels — also contributes to severity staging because malnutrition is a major driver of poorer outcomes.

How Gastroparesis is Diagnosed (tests and what they show)

Diagnosing gastroparesis involves a methodical approach that aims to rule out any physical blockages and assess how quickly the stomach empties:

- Clinical history and physical exam: A provider will evaluate symptom pattern, medication list, surgical history, and comorbid conditions (especially diabetes).

- Upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy): Used to rule out mechanical obstruction (strictures, tumors) that could mimic delayed emptying.

- Gastric emptying scintigraphy, commonly known as a gastric emptying study, is the test that is most frequently recognized. After a standardized meal containing a small radiolabeled tracer, imaging at set intervals (commonly 0, 1, 2, and 4 hours) measures how much of the meal remains in the stomach. Delayed emptying at 2–4 hours supports the diagnosis.

- Breath tests: A non-radioactive breath test using labeled substrates can estimate gastric emptying indirectly and is an alternative at some centers.

- Wireless motility capsule (pH and pressure capsule): A swallowed capsule records transit times through the gut and can identify delayed gastric transit as part of whole-gut motility testing.

- Gastric manometry / antroduodenal manometry: Less commonly used; provides physiologic information about muscular contractions and coordination.

Each test has limitations – for example, gastric emptying can vary with blood glucose levels, recent medications, and meal composition. Diagnosis integrates test results with clinical findings.

Treatment Options: diet, meds, procedures, and devices

Treatment is individualized and typically layered, starting with conservative measures and progressing to medications, endoscopic interventions, or surgery for refractory disease. Goals are to control symptoms, restore or maintain nutrition, prevent complications, and address underlying causes.

Diet and behavioral strategies

Dietary therapy is first-line for most people:

- Small, frequent meals reduce gastric load and nausea.

- Low-fat meals accelerate gastric emptying in many patients because fat delays gastric emptying.

- Diets that are low in fiber or residue decrease the likelihood of food being retained and the formation of bezoars.

- Liquids or pureed meals may empty more promptly than solids and can be more tolerable during flares.

- Nutrient-dense oral supplements can help maintain calories when intake is poor.

Working with a registered dietitian who understands motility disorders improves outcomes and adherence.

Pharmacologic treatments

Medications treat both motility and symptoms:

- Prokinetic agents are designed to enhance stomach contractions and promote faster emptying.Examples commonly used in practice include drugs that stimulate gastrointestinal motility, though availability and regulatory approval vary by region. Benefits must be balanced against side effects.

- Doctors frequently recommend antiemetics to manage feelings of nausea and prevent vomiting.

- Glycemic control medications are crucial in diabetic gastroparesis because high and fluctuating blood sugars worsen motility.

Medication effectiveness varies; many patients get partial relief and some experience side effects that limit use. Long-term decisions should consider risk/benefit and involve specialist input.

Endoscopic and surgical options

For refractory or severe cases:

- Enteral feeding (PEG-J or jejunostomy): When oral intake fails and weight loss or malnutrition is progressive, placing a feeding tube that bypasses the stomach can restore nutrition and reduce hospitalizations.

- Gastric electrical stimulation: An implanted device can reduce refractory nausea and vomiting in selected patients; results are mixed and patient selection is important.

- Endoscopic pyloric therapies (e.g., G-POEM — gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy): This newer procedure targets the pylorus (the stomach outlet) to improve emptying in some patients. Data are growing but long-term outcomes are still under study.

- Surgical options (pyloroplasty, gastrectomy): Reserved for specific indications and selected patients when other measures fail.

Non-pharmacologic and device-based approaches require referral to specialized centers with experience in motility disorders.

Complications That Can Affect Long-Term Outcomes

Multiple complications of gastroparesis directly influence health and life expectancy:

- Malnutrition and weight loss: When caloric intake fails to meet needs, muscle wasting and immune compromise follow. Severe malnutrition increases the risk of infection, delayed healing, and mortality.

- Dehydration and electrolyte disturbances: Recurrent vomiting can cause dehydration, low potassium or magnesium, and cardiac rhythm risks.

- Bezoars: Retained masses of undigested food can obstruct the stomach and cause pain, vomiting, or require endoscopic removal.

- Aspiration pneumonia: Vomiting with aspiration into the lungs can cause life-threatening respiratory infections, particularly in patients with impaired consciousness or swallowing dysfunction.

- Hospitalizations and their risks: Frequent admissions increase exposure to infections, bedrest-related deconditioning, and other iatrogenic harms.

- Psychological effects: Chronic nausea, pain, and limitations in eating commonly contribute to anxiety, depression, and social isolation — all of which affect health resilience.

Preventing or rapidly addressing these complications is central to improving both quality of life and survival.

Does Gastroparesis Shorten Life Expectancy? What the Evidence Says

The relationship between gastroparesis and life expectancy is complex. Broadly:

For the majority of people with gastroparesis, especially those with milder symptoms and preserved nutrition, the condition is more likely to impair day-to-day functioning than to shorten life on its own.

However, gastroparesis can indirectly increase the risk of serious outcomes through malnutrition, aspiration, recurrent severe infections, and by complicating the management of comorbid conditions (notably diabetes). In these situations, how long people live can be affected.

Studies and clinical cohorts indicate that mortality in gastroparesis patients is often tied to coexisting illnesses (cardiovascular disease, advanced diabetes complications, systemic disease) rather than isolated gastric dysmotility. That means prognosis hinges on the whole-person health context, not just the stomach diagnosis.

Clinicians therefore assess prognosis by asking: Is the patient maintaining weight and nutrition? Are severe complications present or likely? Is there a treatable underlying cause? How well are coexisting conditions controlled? The answer to these questions provides a more precise individual prognosis than a single blanket statistic.

Factors That Most Strongly Influence Prognosis

Several factors are repeatedly associated with worse outcomes:

- Underlying cause: Diabetic gastroparesis often occurs with other long-term diabetic complications that influence mortality. Secondary or systemic causes may reflect broader health problems.

- Nutritional status: Ongoing weight loss, low BMI, and low serum protein markers signal higher risk and poorer resilience.

- The likelihood of serious complications: increases with factors such as repeated aspiration, frequent hospital visits, and severe dehydration, which are indicators of poorer results.

- Response to therapy: Patients who can achieve symptom control and improved gastric emptying (or tolerate adequate nutrition with feeding support) have better trajectories.

- Age and comorbidities: Older age and significant cardiovascular, pulmonary, or renal disease increase vulnerability.

- Access to specialized care: Timely referral to motility specialists, dietitians, and tertiary centers for advanced therapies improves options and outcomes.

These factors are actionable: improving nutrition, optimizing control of underlying diseases (especially glucose in diabetes), and early management of complications can change the course for many patients.

Practical Management: Nutrition, Glycemic Control, and Monitoring

Practical strategies that clinicians and patients use to reduce risk and support health include:

Nutrition

- Regular monitoring of weight, calorie intake, and lab markers (electrolytes, micronutrients) is essential.

- Work with a dietitian to construct tolerable, calorie-dense meal plans; consider oral nutritional supplements when needed.

- Transition to liquid nutrition or purees during flares to maintain intake.

- Early discussion about enteral feeding options (PEG-J or jejunal feeding) avoids crisis-driven tube placements and preserves nutritional status.

Glycemic control

- For people with diabetes, tight but safe glucose control reduces autonomic nerve damage progression and can improve motility. Coordination between endocrinology and GI is often necessary because gastroparesis makes glucose management more unpredictable.

- Insulin regimens may require close supervision during changes in diet, vomiting episodes, or when switching to enteral feeding.

Monitoring and follow-up

- Regular symptom assessment, weight checks, and periodic lab monitoring can detect decline early.

- Consider repeat objective testing if symptoms worsen or to evaluate therapy effectiveness.

- Mental health screening and psychosocial support help address the emotional burden, which in turn supports adherence to dietary and medical plans.

Proactive, multidisciplinary care is the most effective strategy to limit complications that drive negative outcomes.

When To Contact Your Doctor or Get Emergency Help

Certain situations require urgent medical attention:

- Inability to tolerate any liquids for more than a day or signs of severe dehydration (dizziness, low urine output, rapid heartbeat).

- Frequent or intense vomiting, making it difficult to hold down medications or fluids.

- Fever with respiratory symptoms or signs of aspiration (cough, shortness of breath after vomiting).

- Rapid, unexplained weight loss or signs of malnutrition (muscle wasting, weakness).

- Severe abdominal pain, bloody vomit, or black/tarry stools — these are red flags for more serious complications.

Having a written action plan and one or two emergency contacts (specialist clinic or hospital) helps patients and caregivers respond quickly.

Living Well: Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Caregiver Tips

Gastroparesis frequently disrupts social life, work, and self-image. Strategies to support living well include:

- Effective meal planning: involves preparing liquid meals in bulk, creating snacks in small portions, and having nutrient-rich shakes ready in the fridge, all of which help to lessen the stress of mealtime.

- Symptom flare plans: Keep antiemetic medications accessible and have a stepwise plan for hydration and when to escalate care.

- Mental health care: Cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups, and counseling can reduce anxiety and depression, improve coping, and sometimes help symptom perception.

- Caregiver organization: Maintain a medication and feeding schedule, weight logs, and a clear list of emergency signs. Caregivers benefit from respite and community resources.

- Work and social adjustments: Flexible work arrangements, explaining needs to family/friends, and pacing social events around meal tolerances can maintain life satisfaction.

Quality of life is a central goal of treatment; even where curing delayed gastric emptying isn’t possible, reducing symptom burden and keeping people nourished and active greatly improves outcomes.

Conclusion

The life expectancy of someone with gastroparesis isn’t a specific, unchanging figure; rather, it varies with the individual and involves more than just the stomach alone. For many people with well-managed symptoms and preserved nutrition, gastroparesis primarily affects quality of life rather than shortening lifespan. However, when the condition causes severe malnutrition, recurrent aspiration, or coexists with poorly controlled systemic diseases (especially advanced diabetes), it can increase health risks and affect long-term survival.

The good news is that many of the factors that influence prognosis are actionable. Early attention to nutrition, close control of underlying conditions, timely symptom management, and access to specialist care can prevent complications that drive worse outcomes. Practical steps, small frequent meals, working with a dietitian, keeping weight and lab markers monitored, having an escalation plan for flares, and seeking multidisciplinary care when needed make a measurable difference.

FAQs

Q: Will gastroparesis shorten my life?

A: For many individuals, gastroparesis impacts their quality of life more than it affects how long they live. However, when it leads to severe malnutrition, recurrent aspiration, or occurs alongside serious comorbidities (especially uncontrolled diabetes), it can contribute to higher health risks and reduced life expectancy.

Q: Can gastroparesis be cured?

A: Some cases improve substantially for example, if a medication is the cause or if an identified reversible factor is treated. Many cases require long-term symptom management rather than a cure.

Q: What foods should I avoid?

A: High-fat and high-fiber foods often delay gastric emptying and can worsen symptoms; carbonated beverages and large, fatty meals are common triggers. A dietitian can customize guidance.

Q: Are there surgical options?

A: Yes options include feeding tube placement for nutrition, pyloric interventions like G-POEM, and, rarely, more extensive surgery. Surgical choices depend on cause, severity, and individual goals of care.

Q: How do I reduce the risk of serious complications?

A: Early nutrition support, good management of underlying illnesses (like diabetes), prompt treatment of infections or dehydration, and regular follow-up with specialists reduce complication risks.